by WWM | Mar 29, 2017 | Risk

Whether managing a business or analyzing a company as a potential investment, nonsystematic risks must be assessed.

An investment in a company may include its stock, bonds, partnerships, or other offerings. A company may also include the mutual, exchange traded, or hedge funds in which you invest. Just because you are planning to invest in Investor Group or Templeton funds does not mean you should ignore nonsystematic risks.

With qualitative analysis, knowledge and experience are key to proper evaluation. Each situation is different and one needs to be mentally nimble to identify the relevant risk factors and how to deal with them.

In two posts, I shall describe typical nonsystematic risks and raise a few of the questions I might ask when assessing a specific risk. The lists and questions will in no way be exhaustive – possibly exhausting for the reader though – but hopefully they will give you an idea of the kind of analysis necessary.

Remember that risk can result in higher than expected returns and not simply losses or lower than expected outcomes. As investors and business people fear negative results, I will concentrate on risk from a negative perspective.

Management Risk

The risk that decisions made by management will negatively impact profitability.

Management of a company may include its Board of Directors, its Officers (senior managers with the legal authority to bind the entity as defined in the corporate statutes), and potentially other managers with lesser authority but key functions in the organization.

Management has a tremendous impact on a company’s actions. Strong management will ensure that prudent decisions are made and that they exert proper stewardship of the company. Weak management will result in the opposite results.

For every company, there is a different management style. Better management improves the probability of success. Poor management increases the risk of loss to an investor.

Note that I do not state that good management brings success and poor management causes loss. Many well-run entities fail and other firms manage to succeed in spite of themselves. There are many other variables that impact a company’s fortunes. Quality of management is just one factor, albeit an important one.

When analyzing a company’s stock or bonds to invest in, management should be a major consideration. This is equally true for investment vehicles such as mutual, exchange traded, or hedge funds you plan to invest in.

For example, ABC investment company has done extremely well over the last 10 years. Their mutual funds consistently outperform their peers. You plan to invest your capital and expect continued high returns. Just before you invest, you read that the primary fund manager resigned to form his own firm and has taken several key analysts from ABC with him.

Is there a possibility that future performance may not reflect that of prior years? If the analysts that discovered the superior investments are no longer with ABC, can ABC continue its success?

What about if Warren Buffet unexpectedly dies? Do you think shares of Berkshire Hathaway will fall upon the news?

Questions to Ask

To address this risk, look at the longevity and performance of the current management team.

Has current management been responsible for past successes or failures?

If the track record of current management is not significant, is there a record for the senior management with their previous companies? Often new management will have been chosen from companies in the same industry. Past performance at a prior firm may indicate success or failure in the new job.

If there is new management, how has the share price moved since the change? If the public sees the change as a positive, the shares should have moved higher. If a negative, the shares may have fallen.

Has there been any recent and/or significant turnover in management? This might indicate a change in corporate philosophy or culture that foreshadows further departures. This could be good (sweeping clean all the dead wood) or bad (all the rats leaving a sinking ship).

For past or planned management changes, has there been a proper succession plan implemented? This helps to ensure that past success will continue with the new management? As Bill Gates stepped back from daily operations at Microsoft, Steve Ballmer assumed greater responsibilities and there were little, if any, continuity issues.

In smaller companies, especially private entities, succession planning is usually a potential red flag issue for investors. Be aware if investing or working in a private or small business.

With mutual funds, I like to see an internal investment culture or philosophy. Not the reliance on one or two gifted managers to produce results.

“Key employee risk” is crucial when I look at any companies or funds. It is something I also strive to minimize in organizations that I have managed.

Operational Risk

Operational and Management Risk are often combined in analysis. They overlap because management decisions directly affect the operations of an organization. But we will keep them separate in this discussion.

Operational risk is the risk associated with operating the specific business.

Specific risks differ for each company due to their unique nature. Even within a single company, changing events may create a wide variety of new operational risk issues.

For example, consider a mining company.

A cave-in occurs underground, injuring several miners. Besides the human factor, there are insurance and legal concerns. Production may be disrupted while the mine is repaired. There may be a negative impact on the company’s reputation. All these ancillary issues that result from the single cave-in may impact profitability (and your share value) over time.

The company has labour contract difficulties and the union votes to strike. Production is shut for six months. This significantly impacts profitability and hurts the share price.

Finally, the mining company decides to hire two employees, Ken Lay and Bernie Madoff, to manage its hedging activities. Within a year, the company is bankrupt and being investigated by the regulators.

These are examples of operational risks.

Assessing operational risk may not be an easy task.

I recommend when analyzing each company or investment to list every possible operational problem that could arise.

Remember that the operational risk factors in one company may be significantly different from those in another entity. You cannot take a cookie-cutter (i.e. identical) approach when analyzing every company.

For each potential risk, consider what steps have been taken to minimize their impact should they arise.

The worse the potential outcome on the business or share price, the more focussed should be your consideration.

Questions to Ask

In keeping with the mining company example, one might ask what is the safety record?

While no guarantee, a strong history of safety indicates that the company is serious about the issue and that should reduce the probability of future problems. Another company that has been fined for safety violations may have learned their lesson. Or they could continue to be a future risk.

Are labour problems and production disruptions common within the company or industry? If so, you might have to endure periods where the company cannot produce their product which will cause financial difficulty.

Have there been regulatory or other issues arise? In the mining industry, one must be concerned about environmental violations that can result in fines, legal costs, clean-up costs, production shut-downs, etc.

Does the mining company operate in a geographic region that may cause financial problems? Some companies operate in difficult areas, such as mountainous terrain or the far north. The more difficult the mining conditions, usually the greater the cost of extraction. This lowers margins and profitability.

Or the company may be operating in a non-business friendly country. If so, there is the possibility of being harassed by the local government, up to and including nationalization of the company’s assets.

The list of potential operational risk issues is endless.

Focus on those that can have the greatest impact on profitability.

Competitor Risk

Competitor risk is that your competition will do something that negatively impacts your business.

A few years back, the Sony Walkman was the norm for portable music. Then along came something called the iPod and the music world changed.

You used to buy your books from the local bookstore. Today you are much more likely to purchase them from Amazon. Your bookstore is now the place to enjoy a Starbucks’ coffee and do some browsing.

Just because a business model has been successful in the past, does not mean that it will continue to be profitable. When considering investments, bear this in mind.

Questions to Ask

Knowing what competitors are up to may not be a simple task.

Media reports, news releases, and reviewing competitors’ financial statements are good ways to follow their activities.

But you should also look at your own company (or the one you want to invest in).

What is your company doing to ward off the competition?

Are there any barriers to entry for competitors? The greater the barriers, the safer the product or company.

The iPhone is extremely popular, but there is nothing to prevent other companies from developing their own smart phones. In fact, over time there became a variety of alternatives to the iPhone.

Strong barriers to entry include patents on key products or processes, sectors that are expensive to enter, and industries that are heavily regulated and/or where there are monopolies present.

Examples include a pharmaceutical company with a long-term patent on a new cancer drug. Or perhaps you want to challenge the American auto makers. However, the cost of entering the auto industry is extremely high. Or you think you could do a better job than the local water company. Unfortunately, the water authority probably has a monopoly on the market and you cannot legally open a business in competition to them.

That should be more than enough for today.

Next, we will look at a few more examples of nonsystematic risk.

by WWM | Mar 24, 2017 | Risk

When making investment decisions, one must consider the expected returns and involved investment risks. Yes, a few other things too, but baby steps. We will get there in due course.

In assessing potential investments, most investors perform both quantitative and qualitative analysis.

Note that investment decisions include financial instruments such as stocks and bonds. But it also refers to any decisions you make when operating a business. Do I buy or rent my office space or production equipment? Do I develop and market a new product? Do I move into a new geographic region? These are also investment decisions.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis is number crunching.

Think of it as quantitative equals quantity.

You take raw data, perform specific calculations, and arrive at a hard number.

Quantitative analysis attempts to be objective and without bias. That is, for a given set of data, different individuals should arrive at the same conclusion.

With investment risk, calculating the standard deviation is an example of quantitative analysis.

Some people fall in love with quantitative analysis. It is reassuring to get objective results that can be directly compared against multiple investment options. Plus it is nice to be able to “blame the numbers” when you make the wrong decisions.

For example, two possible investments both have 10% expected returns. You perform the proper calculations and find that investment A has a standard deviation of 5%, while investment B has one of 8%. You “know” that investment A is the less risky option. That provides comfort when choosing A.

While I agree that quantitative analysis is important, I am leery of relying solely on it.

As we saw, there are limitations to the use of standard deviations. The same is true for most quantitative analysis.

Often, historic data is a key input for quantitative analysis. Yet past results are no guarantee of future performance.

When modelling future results, variable inputs (e.g. inflation, growth rates, etc.) must be determined. These require forecasts and projections of the future. Even the best of estimates may not be wholly accurate.

While quantitative analysis is very useful, it should never be used as the only means of decision-making. You also need to deal with qualitative aspects to get the whole picture.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis is more “touchy-feely” than quantitative analysis.

Whereas quantitative analysis tries to be objective, qualitative analysis is subjective.

Think of it as qualitative equals qualities of the investment.

There are no hard numbers that you can calculate in order to arrive at your decisions. The information is there, one just needs to know how to find it. Usually experience and intuition are key factors in arriving at the correct results.

What one person may discern may be completely different than another might find. Obviously this is an area where competent investment professionals can add value. The more experienced, knowledgeable, technically proficient an asset manager is, the better they should be to assess an investment’s “soft” characteristics.

Now do they get it right often? And/or at a cost to investors that is reasonable? Those are the concerns in the active management versus passive debate.

In the realm of qualitative analysis are the two major components of investment risk. Although they are called a variety of names, we will use the terms nonsystematic and systematic risk.

Each investment decision has components of both nonsystematic and systematic risk. If you can learn to identify the key subsets of these two risk components, you will have an advantage over others when making decisions.

Today we will briefly describe both components. In subsequent posts, I shall identify some of the more common subsets of each class and ways to deal with them.

Nonsystematic Risk

Nonsystematic risks are unique to a specific company, industry, asset, or investment.

Note that when I use the term “company”, for ease in writing, I shall also include sole proprietorships, partnerships, joint ventures, etc. under this heading. If there are any differences worth noting, I shall split them out at that point in time.

Nonsystematic risks may also be called specific, non-market, security-related, idiosyncratic, residual, unique, unsystematic, or diversifiable risk.

The oil company you invested in drills a dry hole. A key employee in your company quits. Your home’s hot water tank explodes, flooding your house. All specific risks.

Systematic Risk

Systematic risk is derived from risks that effect the entire market or a specific segment of the market. Systematic risk factors are far reaching and impact all companies or other investments to some extent.

These factors are not unique to the investment under consideration. They will impact a company regardless of how the company operated or manages its risks.

Systematic risk may also be called non-diversifiable, non-controllable, or market risk.

A global glut of oil drives crude prices down, which in turn lowers the value of your oil company stock. A hurricane hits your home on the Gulf Coast causing significant damage. These are more systematic and non-controllable risks.

Dealing With Nonsystematic and Systematic Risk

For passive investors (i.e., investors of financial instruments), minimizing nonsystematic risk factors is not difficult. By adequately diversifying your investment portfolio, you can effectively manage nonsystematic risks.

Some academics believe that by holding between 12 and 18 stocks (or bonds), one can achieve adequate diversification to eliminate nonsystematic risk. Yes, but they need to be the perfect mix of assets. When we discuss portfolio creation later on, I will review how to properly diversify an investment portfolio.

I think that for most readers living in the real world and not academia, you will need a few more investments to minimize nonsystematic risk. For example, perhaps 40 or more stocks with the right mix. If you only have investable capital of $100,000 you will own 40 companies each with $2500 in stock. The transaction costs, rebalancing expenses, and time to monitor 40 companies can add up.

However, if you invest in a single well diversified exchange traded or mutual fund, you can easily exceed 40 companies in one investment. Usually at very reasonable expense ratios.

Consider Vanguard’s Total World Stock ETF (VT). In this one ETF, you can invest in nearly 8000 companies, located in 47 developed and developing markets around the world. According to Vanguard’s fact sheet, that covers “more than 98% of the global investable market capitalization.” And the annual expense ratio on this fund is only 0.14%. Talk about inexpensive, global diversification (and minimization of nonsystematic or stock specific risk).

That is one of the main reasons that funds should form the core of most investors’ portfolios. You can get great diversification at low cost. Something that is very hard the less capital you have to invest.

For those managing a business, it is impossible to diversify one company. However, by being able to identify the nonsystematic risks, you can take steps to reduce their potential impact. We will look at the specific risks and how to deal with them in my next post.

As some of the alternate names suggest, systematic risk is more difficult to manage. Although sometimes called non- diversifiable or non-controllable risk, you can actual take measures to reduce this risk. Diversification, insurance, and hedging are examples of ways to address systematic risk. When we look at portfolio construction, I will make suggestions on dealing with systematic risk issues.

Next up, a deeper examination of nonsystematic risk.

by WWM | Mar 16, 2017 | Investor Profile, Risk

In Standard Deviation Limitations, I noted that one potential weakness is human behavioural characteristics.

The risk tolerance of each individual is different. It is based on one’s experiences, desires, needs, objectives, and attitudes.

Understanding a person’s unique risk tolerance is critical. How investors view the risk and associated expected return of investments will guide their investment strategy. Everyone differs to some extent.

Today we will look at few questions that shape an individual’s perception of risk.

Consider how you perceive risk as we go through these questions?

Is risk the losing of invested capital?

For many, the thought of losing money is their greatest fear.

These investors typically consider the risk of losing money in absolute dollar terms as compared to the original cost of the asset. Some investors feel that money is only “lost” when the investment is actually sold. Others feel the pain even for losses that are not yet realized.

When we looked at risk, we saw that the greater the investment risk (i.e., standard deviation), the greater the volatility of the investment. That is, the greater the probability that the actual return would deviate from the expected return.

If you fear losing money, you might be more comfortable investing in extremely low risk assets. Sacrifice potentially higher returns for certainty, as well as minimizing the risk of actually incurring an absolute loss.

Is risk the unfamiliar?

Individuals often fear the unknown.

For investors, investments with which one has little or no knowledge of, or appear to be complex in nature, may be seen as riskier.

A good example is the writing of covered call options. Many investors have no experience dealing with options. The mechanics and even the terminology may be intimidating. If I suggested that they incorporate covered calls in their investment portfolio, most investors would be hesitant. Their uncertainty is internalized as increasing the investment risk.

But that is simply the perception. The reality is that covered call options can be an excellent tool within one’s portfolio. While not something I might recommend initially for investors, as investment knowledge and experience improves, one can see that certain options strategies are not risky nor overly complex to execute.

While it is fine to be cautious with unfamiliar investments, that does not necessarily mean they are more risky. Take a little time to learn about areas where you have no knowledge. You might find that the investment is not as risky, nor intimidating, as your initially thought.

Is risk being once bitten twice shy?

Individuals often view investments on which they have previously lost money as unattractive or riskier than they really are.

For example, you purchased 10 ounces of gold in 2012 at USD 1600 per ounce. The investment fell over time and you sold in 2015 for USD 1100 per ounce.

In 2017, you read that gold is recommended as a great mid to long term investment. Based on your prior experience losing money on gold, there is a strong probability you will find this new recommendation unattractive or high risk.

However, that unattractiveness or increased risk is merely a perception and not reality. Whether you gained or lost money on a specific investment in the past has no connection with how well you will do in the future.

Of course, I also meet investors who like to jump back in on investments they previously lost money on. Payback, they are due, karma, pick your reasoning.

Is risk not following the crowd?

Following the conventional wisdom and expert recommendations is usually comforting.

It is always good to find that others, especially experts, agree with your investing decisions. Or that your decisions are based on the consensus of many who may be “smarter” than you. If you lose on the investment, you can take some solace knowing that many others did so as well.

Taking contrary investment positions is more stressful to many individuals. Going against the tide may be seen as a risky proposition. After all, who are you to know more than everyone else?

For example, if the “talking heads” on the business channels are all recommending avoiding Canadian natural resource equities, it takes a bit of nerve to go out and buy shares in these companies.

Given the track record of many “experts”, I am not sure following their advice is often wise.

Investment bubbles are often the end result of following the crowd and engaging in “herd mentality”.

Is risk historically based?

Finally, investors often focus on the past when assessing risk.

Individuals consider historic returns when extrapolating into the future. While history can be a predictor of the future, it is the expected returns (and associated risk) that is more important.

Situations change, both good and bad, and that can impact the risk of an investment.

Consider a mutual fund whose mandate is shares in mining companies. Performance over the last 10 years averaged 15% and risk standard deviation was 4%. Well ahead of other funds in the same category. Based on past results you invest.

However, six months ago the fund decided to sell its investments in traditional mining companies and focus on higher risk companies in Africa and South America. Specifically, countries with less stable companies, young free-market economies, and inefficient markets. Unhappy with the shift in strategy, the successful management team quit. To save money, the fund company has the managers of their banking mutual fund take over management of the mining fund.

Although historic risk was 4%, these recent factors will significantly increase risk levels in the near future.

Data comforts investors in their decision making. And it should. But if you rely too much on the past, you might err in the future. Historic statistics are only applicable if the circumstances in which they occurred are still relevant going forward.

That is why in every mutual fund prospectus you will see “past performance is no indicator of future results.” Or similar.

How did you respond to these questions?

The answers will help you arrive at your personal risk tolerance level. This will guide you as to investments you are comfortable to invest your capital in.

Do you fear the risk of a real loss? Or do you take (hopefully, calculated and prudent) risks to attain potentially higher returns?

Do you avoid the unfamiliar? Or are you an adventurer who seeks out new investment ideas?

Does a prior loss in an asset class or investment cause you to shun them in future? Or is it a chance for revenge?

Do you get comfort relying on experts and the consensus or do you prefer going against the flow?

There are no “right” answers. How you see risk is based on your life history.

However, while risk tolerance levels are unique to each person, I would like to influence each of you to some extent.

I cannot do much about your personality, life experiences, investment objectives, personal constraints, etc. And how they all impact your risk tolerance.

However, I hope to show you that it is best to take a view of risk with as little emotional involvement as possible. That by improving your base investment knowledge and learning what questions to ask, you can become more objective in your decision making.

I fully realize that this is a challenge for almost all individual. But if you can develop a more disciplined approach to investing, you will be in better position to succeed over the long run.

by WWM | Mar 10, 2017 | Risk

While standard deviation is indeed very useful in assessing investment risk, there are limitations to its use.

In analyzing any investment, smart investors factor in these potential weaknesses, including: asymmetric payoffs; historic versus future results; the need for context; human behavioural traits.

Awareness of these potential pitfalls will help you better incorporate standard deviation calculations in your own analysis.

Asymmetric Payoffs

In our previous discussion, we used examples with normal distributions. There was a reason for that. Standard deviations are poor tools for investments with asymmetric payoff profiles.

In a normal distribution, the payoff profile is symmetric. The normal distribution curve should look the same on both sides of the mean. Results should be equally disbursed around the middle. The tails on each end of the curve are symmetric. That is why one can use multiples of the standard deviation (e.g. 2 standard deviations from the mean contains 95% of all potential results) to determine outcome probabilities.

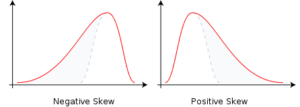

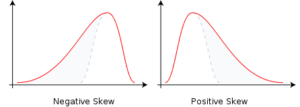

In an asymmetric profile, the distribution curve is skewed on one side of the mean or the other. By skewed, I mean that the tails are unequal in the distribution outcomes.

If the left side tail is more pronounced, there are more actual results to the right side of the mean. But a relatively few extremely small valued outliers drag the tail of the curve leftward. This is being “negatively skewed”.

If the right side of the curve is longer, there are more results on the left side of the mean. But a relatively small number of extremely high value outliers push the tail to the right. In this case, the distribution would be “positively skewed”.

It is easy to see why skewed distributions limit the usefulness of the standard deviation as a risk measurement. In the graphs above, say the mean is 10 and the standard deviation is 2. Under a normal distribution, 68% of results should lie between 8 and 12. 95% of outcomes between 6 and 14. But, as you can see in these two graphs, the distribution pattern is not symmetric. So it is unlikely that the results will fall in the range as intended for standard deviation to be helpful in analyzing the investment.

In the real world, positively skewed distributions are more common than negative ones.

A Real-Life Example of Skewed Distributions

Employee compensation is a typical example. You have 100 people in a company and the average, or mean, salary is $50,000. Of the 100 staff, most likely earn close to that $50,000. Some will make less than the average. But even the most junior staff will earn a minimum level, perhaps $10,000 to $20,000. That is the tail on the left side of the curve.

If compensation was normally distributed one would expect senior management to receive approximately $80,000 to $90,000. A similar “distance” from the mean as the lower junior staff. That creates a nice symmetric, bell shaped curve.

In reality, the President and direct subordinates may earn substantially more. In this example, say the President earns $325,000 and the three Vice-Presidents earn $225,000 each.

Senior management is very few in number, but they distort the distribution curve in two ways.

One, total compensation is $5 million (100 staff averaging $50,000 each), yet only 4% of all employees earn 20% of the compensation (4 senior staff make $1 million combined). That inflates the overall mean relative to the typical employee.

If you eliminated those 4 from the calculation, there would be 96 staff earning $4 million. This results in an adjusted mean of only $41,667 for non-senior management employees. Probably a more realistic figure to compare employee averages. Most staff will earn closer to this average.

Two, the very small number of extremely high value earnings will lie on the far right side of the distribution. These salaries push the curve much farther to the right than if all compensation was normally distributed. The average will be further right than the peak of the curve. This results in the long right-hand tail and the positive skewing of the distribution.

You can likely think of many more examples of where outcomes are not symmetric in reality.

In the realm of investing, option strategies and portfolio insurance are examples of asymmetric payoff profiles.

Not areas we shall delve too deeply. However, I wanted to properly explain asymmetric distributions to further reinforce the understanding of normal distributions.

The Past is Not the Future

A second issue with standard deviations is their use of historic data. Past results might be a predictor of the future, but results may also change over time.

New management, different product lines, increased competition, expiration of patents, etc., all may impact future results and therefore alter the standard deviation.

Be careful in placing too much faith in historic results.

Standard Deviations Need a Context

Standard deviations should never be considered on their own. One needs to factor in the expected return as well.

For example, investment A has a standard deviation of 6%. Investment B has a standard deviation of 10%. If you only look at the standard deviation, B is the riskier investment.

But what if I also tell you that the expected return for A is 4% and 15% for B?

At a 95% confidence interval below the expected return, you could actually lose more with investment A than B. Without getting into the calculations, you could lose 5.9% with A and only lose 1.5% with B.

To address this issue, you need to consider the concept of “Value at Risk”. We may or may not get into this slightly more complex topic at a later date. But no promises or threats.

Human Behaviour

Standard deviations are unable to quantify behavioural aspects of investing risk.

We will devote some time to Behavioural Risk issues at a later date. In essence, it looks at how human behaviour affects the investing decision-making process .

It is an interesting and important topic. And it will not put you to sleep.

So there is a quick overview on the limitations of standard deviations as a risk measure.

You will not need to calculate means or standard deviations. But it is important to know what they are and why they are useful. Then, when you do encounter them, you understand the value and limitations of both measurements.

by WWM | Mar 3, 2017 | Risk

Let’s continue our look at Investment Risk in Detail.

In the last post, we ended with an example. Two investments with the same 5% annual expected return. “A” had a stable return history, so the probability of earning the 5% next year is high. However, “B” had a highly volatile return history, so the probability of earning exactly 5% next year is low.

Same expected annual return over time, but much different likelihoods of actually earning the 5% return in any one year.

As an investor, how does one differentiate between the two investments?

A very important question. Hint: it may involve investment risk.

Standard Deviation

In comparing two investments with the same expected return, it is extremely useful to quantify the investment risk.

And remember, investment risk is simply the volatility of an asset. High certainty of future returns as expected, low risk. Wide fluctuations in returns versus expected, high risk.

To be of any practical use, a measure of risk must have a definitive value that may be analyzed by investors. Standard deviation is the statistical measurement of the movement of returns around the mean.

In investing terms, the standard deviation is the measure of the total risk of the investment.

Under a normal distribution, the majority of actual returns will occur relatively close to the mean or expected return. This is good for predicting future results.

In a normal distribution, 68% of all returns will fall within 1 standard deviation of the mean. 95% of all returns will take place within 2 standard deviations of the mean. 98% of all returns will occur within 3 standard deviations of the mean.

Say the mean is 10 and standard deviation is 3. As 68% of results occur within 1 standard deviation from the mean, that equates to between 7 and 13. While 95% of the time, results will lie within 2 standard deviations. So, between 4 and 16.

This is consistent in any normal distribution.

Nice to know the range of possible results with 95% confidence. Makes investment analysis easier.

If you are concerned about negative returns, in a normal distribution, there is only a 2.5% probability that the next year’s actual return will be lower than 2 standard deviations from the mean. That is good to know.

Note that there is a 95% probability that a return will fall within 2 standard deviations of the mean. So there is a 2.5% probability that next year’s return will exceed 2 standard deviations (i.e. the far right tail of the curve) and a 2.5% chance that the return will be below 2 standard deviations from the mean.

Theory, theory, theory. Let us look at how this applies to real world investing.

An Example of Standard Deviation

Perhaps you have two investment choices. “A” offers an expected return of 10% over a one year period. “B” offers an expected return of 13% over the same period.

Ceteris paribus (all else equal), “B” should be your choice as it offers a higher expected return than “A”.

But all else is never equal, except in Latin phrases.

You notice during your research that each investment has a standard deviation assigned to it. “A” has a standard deviation of 2. “B” has a standard deviation of 9. You also note that both investments have normal distributions.

So how can standard deviations help your investment decision?

Remember that 68% of the time, actual returns will lie within 1 standard deviation of the expected return and within 2 standard deviations 95% of the time.

“A” has an expected return of 10% and a standard deviation of 2. That means 68% of all possible returns actually achieved will be between 8% and 12%. And that 95% of the time you will experience returns between 6% and 14%.

A fairly stable distribution of returns over time. Not a volatile asset, “A” has a relatively low standard distribution.

For investors worried about experiencing a loss or lower than desired returns, 95% of the time they will, at worst, earn a 6% return. Nice to know if you are worried about absolute losses.

“B” has an expected return of 13% but a standard deviation of 9. 68% of results will lie between 4% and 22%. And 95% of the returns will be between -5% and 31%.

“B” is much more volatile in its returns than “A”. This is reflected by the higher standard deviation value.

Very nice upside potential of 31% return. But if concerned about lower potential returns or even losses, “B” might be too risky with it’s potential -5% return.

Armed with this new standard deviation information, does your investment decision change?

It might, it might not.

Investment Risk is a Relative Concept

As we discussed previously, the concept of risk is different for every individual.

Risk is therefore a relative term, not an absolute.

Some investors want to limit their downside investment risk and any possibility of experiencing a loss. Widows and orphans are in this group. As are many other investors.

These individuals willingly accept a lower expected return in exchange for a greater certainty of that return being realized. Investments whose potential returns are less volatile or variable are desired. A less risky result is preferable to higher potential returns (and more downside risk).

Other investors might be lured by the potentially high returns of “B”. Option “A” should rise no higher than 14% (97.5% of the time), whereas “B” could beat that return easily (of course, it could also do significantly worse as well).

Risk Aversion Versus Risk Seeking

While each investor takes a different view of risk, most investors (as opposed to speculators, who we will discuss later) tend to be risk averse. That is, when faced with two investment choices of similar return, they select the less risky one.

In contrast, risk seekers will actively assume greater levels of risk in the hopes of achieving higher returns. Their risk tolerance is significantly higher than risk avoiders.

In the capital markets, you need some investors to be risk seekers and others to be risk avoiders. The system will not properly function if everyone is the same. As we will see later, hedgers actively attempt to reduce their risk exposure. But they need to transfer that risk somewhere. Without risk seekers, there would be no one to assume the hedger’s risk and the markets would be very inefficient.

In the example above, I would suggest “A” is the better choice based solely on the information given. I say that because the relatively greater expected return of “B” is not large enough to warrant the significantly higher level of risk you must assume. So while I have no problem with risk seekers as an investor class, risk should be assumed prudently.

A Rule to Remember

“When faced with two investments offering identical expected returns, investors will always choose the one with less risk.”

Or stated another way:

“When faced with two investments having identical risk, investors will always choose the one with the higher return.”

Of course, the issue is choosing between two investments when they have different expected returns and standard deviations. A more likely scenario in the real world. And the choice usually comes down to the individual investor’s risk tolerance and unique personal circumstances.

In the near future we will look at the risk-return relationship and the implications of risk aversion and risk seeking on investment decisions. After which, please revisit this example and see if your original opinion has changed at all.

Regardless of your personal risk profile, the standard deviation of an investment is a very useful piece of information to have at hand. But be aware that there are limitations to the use of standard deviations.

We will look at these limitations in my next post.