by WWM | Mar 21, 2017 | Investor Profile

“What is Your Risk Tolerance?” asked a few questions to help determine your risk comfort level.

I want to flesh those questions out using a classic investor personality model, the Bailard, Biehl, & Kaiser Five-Way Model.

I am not a “fit in a box” guy. It is rare to find someone who is an exact match within any personality model. But understanding how your general tendencies impact your decision making is useful. Learning more about who you are as an investor will ease your shift to become a more unemotional, objective, and successful investor.

Investor Psychographic Models

Investor psychographic models can help investors determine their own risk tolerance.

Pyschographics refers to the description of an individual’s psychological characteristics. It attempts to classify investors based on their personality traits.

There are a variety of models in use today. I suggest you review a couple of models to better understand your own investor profile. In this post, we shall look at the Bailard, Biehl, & Kaiser Five-Way Model.

The key to this model is that it focuses on two personality traits: investor confidence level and preferred method of action.

Investor confidence may range from being totally confident to being wholly anxious in investing abilities.

An investor’s method of action considers how methodical, analytical, and intuitive an investor is in his actions. One’s method of action may range from extreme carefulness or caution to being highly impetuous or reckless.

Confidence and method of action are plotted on two axes and investors are grouped according to their preferences. In this model, there are five possible investor profiles.

Guardians

Guardians are extremely cautious and anxious in their behaviour. Preservation of capital is paramount. Guardians are very risk averse and do not want to incur any monetary losses.

Often, older investors fall into this category. Older investors need to preserve their assets and usually want secure investments with a steady, stable income flow.

That said, new investors may also fall into this category. As knowledge and experience levels are very low, new investors may want to take a cautious and safe investment approach until they gain sufficient skill to move into riskier assets.

Guardians typically invest in government backed bonds or treasury bills, term deposits, preferred shares in public companies, and balanced mutual funds. Low risk of capital loss, but with little hope of significant capital gains.

Celebrities

Celebrities are investors who are anxious but, at the same time, are also impetuous. Not a combination that usually results in long term success.

Celebrities exhibit a crowd mentality and like to invest in the latest hot investments.

For example, if gold is in vogue amongst the media talking heads, Celebrities will invest in gold. Or if a friend at a cocktail party mentions some new biotech company, the Celebrity will want to purchase shares as well.

Whether the investment in question is potentially positive from an analytical perspective or whether it is appropriate for the specific investor are usually not considerations for the Celebrity.

Celebrity investors may be of any age group although I suspect more fall into the young or middle age groupings. This is because over time, Celebrities will not usually be financially successful following this path and move on to more structured investment approaches (or they will have lost all their capital).

Celebrities invest in a wide variety of assets, usually creating a haphazard portfolio. One that tends to be of higher volatility. The only common theme is that the investment is currently fashionable. That often excludes investments in plain-vanilla (i.e. boring) assets such as term deposits, treasury bills, and balanced mutual funds.

Can you just picture a Celebrity discussing his 90 day term deposit at the local bank when all his friends are raving about their shares of Albanian hi-tech companies? Neither can I.

Celebrities are prime candidates for getting caught in an investment bubble.

Adventurers

Adventurers are highly confident, but impetuous.

Adventurers are strong-willed individuals who may be entrepreneurs in their work life. Often successful in business, they expect that success will flow into other areas of their lives. The difficulty is that these individuals do not typically have the time nor the inclination to develop the necessary tools to also become successful investors.

As a result, Adventurers may act rashly and err in their investing decisions.

Adventurers are willing to take chances on their investments and readily consider higher risk assets that offer better potential returns. This would include smaller public or unlisted companies, real estate, venture capital, and derivatives.

Diversified portfolios are considered boring. Adventurers are comfortable investing a significant portion of their assets in one single investment.

Individualists

Individualists are strong willed and highly confident, but they act with care.

Individualists are very rational and analytical in their investing strategies. They understand the relationship between risk and return and take emotions out of their investing style.

Individualists are normally “do-it-yourself” investors, performing their own research and making their own decisions.

As they act with caution and not recklessness, Individualists make less fundamental investment errors than Adventurers.

Individualists invest in a wide variety of assets and develop diversified portfolios. They also tend to be contrarian in their approach and typically have an eye for value. Because of this, individualists may be able to avoid investment bubbles.

Professional investors normally fall into this investor category.

Straight-Arrows

By their vary nature, models tend to classify investors into extremes. In actuality, most investors fall somewhere in between the outer reaches.

Into this comes the Straight-Arrow classification. Where the “average” investor, who possesses some investment experience and knowledge, tends to sit.

Straight-Arrows do not clearly fall into any one category. There is overlap between the different classifications.

Straight-Arrows have some confidence. Not the total level of an Adventurer or Individualist, but substantially more than exhibited by the Guardian or Celebrity.

Straight-Arrows act in a reasonable manner, for the most part. They normally act in a prudent and careful manner, but are still prone to recklessness and following the herd at times.

A Straight-Arrow should be open to investing in a wide variety of asset classes.

And You?

Where do you fit into this Five-Way Model?

Ideally, as an investor, becoming an Individualist is the best case scenario.

For most people who are not professional investors, finding the time and energy to become an Individualist is not usually possible. For these people, becoming a Straight-Arrow should be the goal to best achieve one’s investment objectives.

Straight-Arrows can prosper relying on a structured investment strategy incorporating a passive asset management style.

Straight-Arrows also benefit when working with a professional financial advisor. Straight-Arrows have an understanding of investing and can work in partnership with a professional to develop and implement a prudent investment plan.

If you are currently more of a Guardian, Celebrity, or Adventurer, no worries at this time. By understanding the weaknesses of each category, you can take conscious measures to eliminate the deficiencies in your investor profile and move toward a more well-rounded approach.

I understand that changing basic personality traits may not be easy. Some people are naturally anxious while others are confident. Some are cautious, others are rash. It is all part of one’s inner make-up.

Over time, I hope you will see that a rational approach to investing is the best way to invest. If you do, that will provide you with greater confidence and the ability to take on a more measured course of action in your investing activities.

by WWM | Mar 16, 2017 | Investor Profile, Risk

In Standard Deviation Limitations, I noted that one potential weakness is human behavioural characteristics.

The risk tolerance of each individual is different. It is based on one’s experiences, desires, needs, objectives, and attitudes.

Understanding a person’s unique risk tolerance is critical. How investors view the risk and associated expected return of investments will guide their investment strategy. Everyone differs to some extent.

Today we will look at few questions that shape an individual’s perception of risk.

Consider how you perceive risk as we go through these questions?

Is risk the losing of invested capital?

For many, the thought of losing money is their greatest fear.

These investors typically consider the risk of losing money in absolute dollar terms as compared to the original cost of the asset. Some investors feel that money is only “lost” when the investment is actually sold. Others feel the pain even for losses that are not yet realized.

When we looked at risk, we saw that the greater the investment risk (i.e., standard deviation), the greater the volatility of the investment. That is, the greater the probability that the actual return would deviate from the expected return.

If you fear losing money, you might be more comfortable investing in extremely low risk assets. Sacrifice potentially higher returns for certainty, as well as minimizing the risk of actually incurring an absolute loss.

Is risk the unfamiliar?

Individuals often fear the unknown.

For investors, investments with which one has little or no knowledge of, or appear to be complex in nature, may be seen as riskier.

A good example is the writing of covered call options. Many investors have no experience dealing with options. The mechanics and even the terminology may be intimidating. If I suggested that they incorporate covered calls in their investment portfolio, most investors would be hesitant. Their uncertainty is internalized as increasing the investment risk.

But that is simply the perception. The reality is that covered call options can be an excellent tool within one’s portfolio. While not something I might recommend initially for investors, as investment knowledge and experience improves, one can see that certain options strategies are not risky nor overly complex to execute.

While it is fine to be cautious with unfamiliar investments, that does not necessarily mean they are more risky. Take a little time to learn about areas where you have no knowledge. You might find that the investment is not as risky, nor intimidating, as your initially thought.

Is risk being once bitten twice shy?

Individuals often view investments on which they have previously lost money as unattractive or riskier than they really are.

For example, you purchased 10 ounces of gold in 2012 at USD 1600 per ounce. The investment fell over time and you sold in 2015 for USD 1100 per ounce.

In 2017, you read that gold is recommended as a great mid to long term investment. Based on your prior experience losing money on gold, there is a strong probability you will find this new recommendation unattractive or high risk.

However, that unattractiveness or increased risk is merely a perception and not reality. Whether you gained or lost money on a specific investment in the past has no connection with how well you will do in the future.

Of course, I also meet investors who like to jump back in on investments they previously lost money on. Payback, they are due, karma, pick your reasoning.

Is risk not following the crowd?

Following the conventional wisdom and expert recommendations is usually comforting.

It is always good to find that others, especially experts, agree with your investing decisions. Or that your decisions are based on the consensus of many who may be “smarter” than you. If you lose on the investment, you can take some solace knowing that many others did so as well.

Taking contrary investment positions is more stressful to many individuals. Going against the tide may be seen as a risky proposition. After all, who are you to know more than everyone else?

For example, if the “talking heads” on the business channels are all recommending avoiding Canadian natural resource equities, it takes a bit of nerve to go out and buy shares in these companies.

Given the track record of many “experts”, I am not sure following their advice is often wise.

Investment bubbles are often the end result of following the crowd and engaging in “herd mentality”.

Is risk historically based?

Finally, investors often focus on the past when assessing risk.

Individuals consider historic returns when extrapolating into the future. While history can be a predictor of the future, it is the expected returns (and associated risk) that is more important.

Situations change, both good and bad, and that can impact the risk of an investment.

Consider a mutual fund whose mandate is shares in mining companies. Performance over the last 10 years averaged 15% and risk standard deviation was 4%. Well ahead of other funds in the same category. Based on past results you invest.

However, six months ago the fund decided to sell its investments in traditional mining companies and focus on higher risk companies in Africa and South America. Specifically, countries with less stable companies, young free-market economies, and inefficient markets. Unhappy with the shift in strategy, the successful management team quit. To save money, the fund company has the managers of their banking mutual fund take over management of the mining fund.

Although historic risk was 4%, these recent factors will significantly increase risk levels in the near future.

Data comforts investors in their decision making. And it should. But if you rely too much on the past, you might err in the future. Historic statistics are only applicable if the circumstances in which they occurred are still relevant going forward.

That is why in every mutual fund prospectus you will see “past performance is no indicator of future results.” Or similar.

How did you respond to these questions?

The answers will help you arrive at your personal risk tolerance level. This will guide you as to investments you are comfortable to invest your capital in.

Do you fear the risk of a real loss? Or do you take (hopefully, calculated and prudent) risks to attain potentially higher returns?

Do you avoid the unfamiliar? Or are you an adventurer who seeks out new investment ideas?

Does a prior loss in an asset class or investment cause you to shun them in future? Or is it a chance for revenge?

Do you get comfort relying on experts and the consensus or do you prefer going against the flow?

There are no “right” answers. How you see risk is based on your life history.

However, while risk tolerance levels are unique to each person, I would like to influence each of you to some extent.

I cannot do much about your personality, life experiences, investment objectives, personal constraints, etc. And how they all impact your risk tolerance.

However, I hope to show you that it is best to take a view of risk with as little emotional involvement as possible. That by improving your base investment knowledge and learning what questions to ask, you can become more objective in your decision making.

I fully realize that this is a challenge for almost all individual. But if you can develop a more disciplined approach to investing, you will be in better position to succeed over the long run.

by WWM | Mar 10, 2017 | Risk

While standard deviation is indeed very useful in assessing investment risk, there are limitations to its use.

In analyzing any investment, smart investors factor in these potential weaknesses, including: asymmetric payoffs; historic versus future results; the need for context; human behavioural traits.

Awareness of these potential pitfalls will help you better incorporate standard deviation calculations in your own analysis.

Asymmetric Payoffs

In our previous discussion, we used examples with normal distributions. There was a reason for that. Standard deviations are poor tools for investments with asymmetric payoff profiles.

In a normal distribution, the payoff profile is symmetric. The normal distribution curve should look the same on both sides of the mean. Results should be equally disbursed around the middle. The tails on each end of the curve are symmetric. That is why one can use multiples of the standard deviation (e.g. 2 standard deviations from the mean contains 95% of all potential results) to determine outcome probabilities.

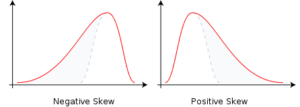

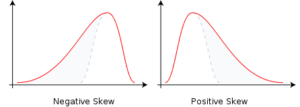

In an asymmetric profile, the distribution curve is skewed on one side of the mean or the other. By skewed, I mean that the tails are unequal in the distribution outcomes.

If the left side tail is more pronounced, there are more actual results to the right side of the mean. But a relatively few extremely small valued outliers drag the tail of the curve leftward. This is being “negatively skewed”.

If the right side of the curve is longer, there are more results on the left side of the mean. But a relatively small number of extremely high value outliers push the tail to the right. In this case, the distribution would be “positively skewed”.

It is easy to see why skewed distributions limit the usefulness of the standard deviation as a risk measurement. In the graphs above, say the mean is 10 and the standard deviation is 2. Under a normal distribution, 68% of results should lie between 8 and 12. 95% of outcomes between 6 and 14. But, as you can see in these two graphs, the distribution pattern is not symmetric. So it is unlikely that the results will fall in the range as intended for standard deviation to be helpful in analyzing the investment.

In the real world, positively skewed distributions are more common than negative ones.

A Real-Life Example of Skewed Distributions

Employee compensation is a typical example. You have 100 people in a company and the average, or mean, salary is $50,000. Of the 100 staff, most likely earn close to that $50,000. Some will make less than the average. But even the most junior staff will earn a minimum level, perhaps $10,000 to $20,000. That is the tail on the left side of the curve.

If compensation was normally distributed one would expect senior management to receive approximately $80,000 to $90,000. A similar “distance” from the mean as the lower junior staff. That creates a nice symmetric, bell shaped curve.

In reality, the President and direct subordinates may earn substantially more. In this example, say the President earns $325,000 and the three Vice-Presidents earn $225,000 each.

Senior management is very few in number, but they distort the distribution curve in two ways.

One, total compensation is $5 million (100 staff averaging $50,000 each), yet only 4% of all employees earn 20% of the compensation (4 senior staff make $1 million combined). That inflates the overall mean relative to the typical employee.

If you eliminated those 4 from the calculation, there would be 96 staff earning $4 million. This results in an adjusted mean of only $41,667 for non-senior management employees. Probably a more realistic figure to compare employee averages. Most staff will earn closer to this average.

Two, the very small number of extremely high value earnings will lie on the far right side of the distribution. These salaries push the curve much farther to the right than if all compensation was normally distributed. The average will be further right than the peak of the curve. This results in the long right-hand tail and the positive skewing of the distribution.

You can likely think of many more examples of where outcomes are not symmetric in reality.

In the realm of investing, option strategies and portfolio insurance are examples of asymmetric payoff profiles.

Not areas we shall delve too deeply. However, I wanted to properly explain asymmetric distributions to further reinforce the understanding of normal distributions.

The Past is Not the Future

A second issue with standard deviations is their use of historic data. Past results might be a predictor of the future, but results may also change over time.

New management, different product lines, increased competition, expiration of patents, etc., all may impact future results and therefore alter the standard deviation.

Be careful in placing too much faith in historic results.

Standard Deviations Need a Context

Standard deviations should never be considered on their own. One needs to factor in the expected return as well.

For example, investment A has a standard deviation of 6%. Investment B has a standard deviation of 10%. If you only look at the standard deviation, B is the riskier investment.

But what if I also tell you that the expected return for A is 4% and 15% for B?

At a 95% confidence interval below the expected return, you could actually lose more with investment A than B. Without getting into the calculations, you could lose 5.9% with A and only lose 1.5% with B.

To address this issue, you need to consider the concept of “Value at Risk”. We may or may not get into this slightly more complex topic at a later date. But no promises or threats.

Human Behaviour

Standard deviations are unable to quantify behavioural aspects of investing risk.

We will devote some time to Behavioural Risk issues at a later date. In essence, it looks at how human behaviour affects the investing decision-making process .

It is an interesting and important topic. And it will not put you to sleep.

So there is a quick overview on the limitations of standard deviations as a risk measure.

You will not need to calculate means or standard deviations. But it is important to know what they are and why they are useful. Then, when you do encounter them, you understand the value and limitations of both measurements.

by WWM | Mar 5, 2017 | Fixed Income

I tweeted today about a Bond 101 Primer courtesy of PIMCO. Well worth a read.

When we reach asset classes in this blog’s investment series, we will go into bonds in detail. A good article, but the PIMCO primer illustrates why I am trying to build up some core investment knowledge before tackling the assets, strategies, and tactics. It is a much better read if you understand diversification, correlations, hedging, and such.

Bonds Get a Lot of Questions

I mention it now as bonds are usually a big question from clients.

Namely, “Why should we invest in an asset class (bonds) that tends to offer weaker expected returns than other classes (e.g. equities)? Shouldn’t we want to put our money in assets with the best expected returns?”

I would not disagree with either question. So why should you invest anything in bonds?

Non-Return Bond Benefits

I like bonds in portfolios for a variety of reasons.

Yes, you can get real returns from bonds, so they are not a waste of capital (though they can be in certain economic conditions). You can also generate substantial capital gains (or losses) from bonds (again, depending on economic conditions). So there are possible returns from capital as well as interest.

But I like bonds in client portfolios for non-return benefits.

Bonds often provide higher stability and certainty of returns than equities. Over time, bonds may earn less than equities, but your risk level should be lower. Preservation of capital may outweigh potential returns for many investors. And, as you approach retirement and plan to live off your savings, having a known income stream is important.

Bonds often are less than perfectly correlated with equities. This enhances portfolio diversification, a desired result.

Bonds may provide hedging opportunities which can be beneficial.

Bonds come in multiple sub-classes in a variety of currencies. Depending on your risk appetite, some bonds may offer potentially lucrative returns versus equities. Tactical bond strategies within the asset class alone can increase returns, reduce portfolio risk, and enhance hedging. You can purchase plain vanilla buy and hold until maturity bonds. Or you can engage in many varied tactics. Bonds offer all things to all investors and can achieve a wide variety of objectives.

I think most investors, even those with extremely long investment time horizons, can benefit with a percentage of bonds in their portfolios. Obviously, the exact proportion fluctuates between individuals, as well as over time for a specific investor, based on unique and ever-changing personal circumstances.

One Other Note

I do suggest taking a look at the PIMCO piece. If you understand all the terminology and concepts, great.

If not, do not worry. The article illustrates what I am attempting to do with my blog posts. Over the next little while, we will lay a solid foundation of investment concepts. Asset correlations, diversification, hedging, etc.

By the time we get into the properties, advantages, and disadvantages of various asset classes, you will easily follow the points. But without the groundwork, probably not as much value diving right into asset class pros and cons.

For example, I tweeted that I tend to favour using bond ladders for the average investor. PIMCO touches on ladders. But when we finish the core concepts and get into fixed income, you will better understand WHY bond ladders may be useful in your portfolio strategies.

To me, it is the understanding why something should be utilized that makes investors successful.

Hopefully, over time, we achieve that together.

by WWM | Mar 3, 2017 | Risk

Let’s continue our look at Investment Risk in Detail.

In the last post, we ended with an example. Two investments with the same 5% annual expected return. “A” had a stable return history, so the probability of earning the 5% next year is high. However, “B” had a highly volatile return history, so the probability of earning exactly 5% next year is low.

Same expected annual return over time, but much different likelihoods of actually earning the 5% return in any one year.

As an investor, how does one differentiate between the two investments?

A very important question. Hint: it may involve investment risk.

Standard Deviation

In comparing two investments with the same expected return, it is extremely useful to quantify the investment risk.

And remember, investment risk is simply the volatility of an asset. High certainty of future returns as expected, low risk. Wide fluctuations in returns versus expected, high risk.

To be of any practical use, a measure of risk must have a definitive value that may be analyzed by investors. Standard deviation is the statistical measurement of the movement of returns around the mean.

In investing terms, the standard deviation is the measure of the total risk of the investment.

Under a normal distribution, the majority of actual returns will occur relatively close to the mean or expected return. This is good for predicting future results.

In a normal distribution, 68% of all returns will fall within 1 standard deviation of the mean. 95% of all returns will take place within 2 standard deviations of the mean. 98% of all returns will occur within 3 standard deviations of the mean.

Say the mean is 10 and standard deviation is 3. As 68% of results occur within 1 standard deviation from the mean, that equates to between 7 and 13. While 95% of the time, results will lie within 2 standard deviations. So, between 4 and 16.

This is consistent in any normal distribution.

Nice to know the range of possible results with 95% confidence. Makes investment analysis easier.

If you are concerned about negative returns, in a normal distribution, there is only a 2.5% probability that the next year’s actual return will be lower than 2 standard deviations from the mean. That is good to know.

Note that there is a 95% probability that a return will fall within 2 standard deviations of the mean. So there is a 2.5% probability that next year’s return will exceed 2 standard deviations (i.e. the far right tail of the curve) and a 2.5% chance that the return will be below 2 standard deviations from the mean.

Theory, theory, theory. Let us look at how this applies to real world investing.

An Example of Standard Deviation

Perhaps you have two investment choices. “A” offers an expected return of 10% over a one year period. “B” offers an expected return of 13% over the same period.

Ceteris paribus (all else equal), “B” should be your choice as it offers a higher expected return than “A”.

But all else is never equal, except in Latin phrases.

You notice during your research that each investment has a standard deviation assigned to it. “A” has a standard deviation of 2. “B” has a standard deviation of 9. You also note that both investments have normal distributions.

So how can standard deviations help your investment decision?

Remember that 68% of the time, actual returns will lie within 1 standard deviation of the expected return and within 2 standard deviations 95% of the time.

“A” has an expected return of 10% and a standard deviation of 2. That means 68% of all possible returns actually achieved will be between 8% and 12%. And that 95% of the time you will experience returns between 6% and 14%.

A fairly stable distribution of returns over time. Not a volatile asset, “A” has a relatively low standard distribution.

For investors worried about experiencing a loss or lower than desired returns, 95% of the time they will, at worst, earn a 6% return. Nice to know if you are worried about absolute losses.

“B” has an expected return of 13% but a standard deviation of 9. 68% of results will lie between 4% and 22%. And 95% of the returns will be between -5% and 31%.

“B” is much more volatile in its returns than “A”. This is reflected by the higher standard deviation value.

Very nice upside potential of 31% return. But if concerned about lower potential returns or even losses, “B” might be too risky with it’s potential -5% return.

Armed with this new standard deviation information, does your investment decision change?

It might, it might not.

Investment Risk is a Relative Concept

As we discussed previously, the concept of risk is different for every individual.

Risk is therefore a relative term, not an absolute.

Some investors want to limit their downside investment risk and any possibility of experiencing a loss. Widows and orphans are in this group. As are many other investors.

These individuals willingly accept a lower expected return in exchange for a greater certainty of that return being realized. Investments whose potential returns are less volatile or variable are desired. A less risky result is preferable to higher potential returns (and more downside risk).

Other investors might be lured by the potentially high returns of “B”. Option “A” should rise no higher than 14% (97.5% of the time), whereas “B” could beat that return easily (of course, it could also do significantly worse as well).

Risk Aversion Versus Risk Seeking

While each investor takes a different view of risk, most investors (as opposed to speculators, who we will discuss later) tend to be risk averse. That is, when faced with two investment choices of similar return, they select the less risky one.

In contrast, risk seekers will actively assume greater levels of risk in the hopes of achieving higher returns. Their risk tolerance is significantly higher than risk avoiders.

In the capital markets, you need some investors to be risk seekers and others to be risk avoiders. The system will not properly function if everyone is the same. As we will see later, hedgers actively attempt to reduce their risk exposure. But they need to transfer that risk somewhere. Without risk seekers, there would be no one to assume the hedger’s risk and the markets would be very inefficient.

In the example above, I would suggest “A” is the better choice based solely on the information given. I say that because the relatively greater expected return of “B” is not large enough to warrant the significantly higher level of risk you must assume. So while I have no problem with risk seekers as an investor class, risk should be assumed prudently.

A Rule to Remember

“When faced with two investments offering identical expected returns, investors will always choose the one with less risk.”

Or stated another way:

“When faced with two investments having identical risk, investors will always choose the one with the higher return.”

Of course, the issue is choosing between two investments when they have different expected returns and standard deviations. A more likely scenario in the real world. And the choice usually comes down to the individual investor’s risk tolerance and unique personal circumstances.

In the near future we will look at the risk-return relationship and the implications of risk aversion and risk seeking on investment decisions. After which, please revisit this example and see if your original opinion has changed at all.

Regardless of your personal risk profile, the standard deviation of an investment is a very useful piece of information to have at hand. But be aware that there are limitations to the use of standard deviations.

We will look at these limitations in my next post.